Artificial disc replacement, (ADR), is only for the few people where back pain cannot be managed by conservative treatment. It is important to remember that this is major surgery – you should not even consider it unless your problem is serious, lasting and unresponsive to sustained non-operative treatments.

The primary aim of ADR is to relieve back pain. If your pain comes from the discs this can be achieved by removing the disc completely and replacing it with an artificial disc or by fusing the adjacent bones together (lumbar fusion). If it comes from the facet joints, the only option is to fuse the bones and stop the movement.

Here we describe the ADR. Some patients need more than one level replacing and some a fusion at one level and an artificial disc replacement at the other. These are mentioned also.

What happens on the day of surgery

Please click here for further details.

The day will begin with you in the ward. Some of you will have come in the night before though increasingly patients come in on the morning of surgery which may mean a very early start, as you are often needed at the hospital by 7am. My office or our Spinal Nurse will be able to tell you when.

Make sure you have your scans – no scan, no operation.

The night before or that morning you will sign your consent form and meet the anaesthetist. This is a good time to give me the telephone number of any relative you would like contacted when the operation is over – we are always happy to do this.

You will have had nothing to eat or drink for a substantial period before the anaesthetic. The precise length of this period, (usually 6 hours), is prescribed by the anaesthetist and you need to be clear about this the day before the surgery. My secretarial team or our Spinal Nurse will clarify this also.

One of the hospital porters will come and collect you from the ward and will take you to theatre, with one of the ward staff. They deliver you, on a trolley, to the anaesthetic ante-room adjacent to the operating theatre.

There you will meet the anaesthetist again. They will usually put a small drip into a vein on the back of the hand. After asking you to breathe some oxygen they will send you off to sleep with an injection into the drip.

The next thing you are aware of is waking up in the recovery area or back on the ward.

How the Operation is Performed

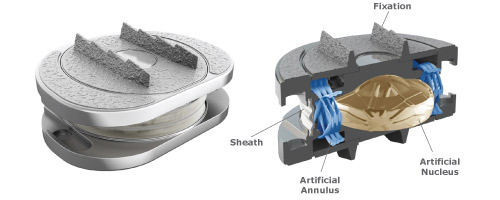

The operation is performed via the tummy through a horizontal incision around or below the “bikini line”. The disc is completely removed and replaced with an artificial disc. Historically, these have been primitive ball and socket joints though they are now highly engineered physiological replicas.

Please click here for details regarding artificial disc replacements

Please click here for details of how the surgery in performed.

How an artificial disc replacement is done

Once you are anesthetised, you are taken through into the operating theatre. You are placed face up on the operating table.

The incision, (cut in the skin), is made on the abdomen, (tummy). Its length is determined by the number of levels involved. By using X-ray guidance, we can keep this as small as possible though these are not “keyhole” operations. The incision usually goes from side to side and is between the naval and the pelvic bone just above or at the pubic hair – a high bikini line.

Occasionally, an up and down incision is needed. If you have had previous surgery we may be able to use those. The muscle is then parted to reveal the abdominal contents. These are contained in a sack called the peritoneum. This is thin and can be seen through. It is kept intact and the intestines are moved over to the right to approach the front of the spine from the left and finally head on from the front. The dissection takes you over the muscles on the back of the abdomen, the arteries and veins supplying the legs, the tube between the bladder and the left kidney and various nerves (more of these later). The bladder would get in the way and be at risk if full so a urinary catheter is put in after the anaesthetic.

We often inject local anaesthetic to numb the area of skin where the incision is to be made and the tissues below. This reduces the amount of painkiller the anaesthetist has to use with the general anaesthetic and makes it safer. The local anaesthetic has adrenaline added so as to constrict the local blood vessels. This decreases bleeding which makes the operation safer and lengthens the effect of the local which makes the immediate post operative pain. This is called “a local block”.

This “access” to the front of the spine is often taxing particularly if there have been previous abdominal or pelvic problems or surgery and several crucial structures are potentially at risk. Thus, often a second surgeon is required to safely access the spine and keep the risks to a minimum. It is our custom to have an “access surgeon” frequently. This will be a vascular surgeon whose day job routinely takes them to this part of the body and is clearly an expert in the principle hazards which are vascular – arteries and veins. Most often this is Mr O. Agu who heads the vascular surgery unit at University College Hospital London. It may be another surgeon particularly if your previous problems have involved specific surgeries requiring a different skill set. Whoever it may be, you will meet them prior to your surgery on the day.

Now comes the business end of the operation. Several things are done.

The disc is cleared. This is the “discectomy”. The bone of the adjacent vertebrae is cleaned meticulously of all disc fragments so that the bone surface will grow into the grafts – see below.

A decompression is completed by removing the thickened bones and ligaments from the back of the disc and this is advanced with the aid of the operating microscope. If the central canal is narrow, the bone and ligaments are cleared from it so as to perform a “central canal decompression”. The foramina (hole) which the individual nerve roots exits from the spine is now widened as necessary. Again, this is done by shaving bone and ligament from the walls as this will have thickened to cause the its narrowing. This called a “nerve root decompression”

There then follows the insertion of the artificial disc replacement. In this option the artificial disc is fitted into the space left by the disc. There are many different artificial discs and we will talk to you about the one you will have. We currently usually recommend the M6L. It has metal end plates in between which there is a composite structure designed to mimic normal disc physiology. They are secured to the ends of the vertebral bones on either side of the disc space in the short term by fins cut into channels in the bone. Longer term, the bone itself grows into micro-pores on the surface of the disc’s metal plates.

(In composite operations, one level is fused and the other replaced a fusion may now follow. A fusion has two elements to it; the instrumentation and the bone graft. The instrumentation involves inserting a cage into the empty disc space between the vertebral bones to be fused. This cage is often secured by a plate and four screws which are placed into the vertebral bones. The bone graft is used to fill the cage and further bone graft is placed around the side of the spine.)

Once this has been completed there comes the “closure”. Again meticulous care is taken to stop any bleeding and the wound is then stitched in layers using internal absorbable stitches. A drain is sometimes placed at the base of the wound. This is rather like a drip and is removed at 24 hours. The skin may be closed in a number of ways though most commonly an absorbable stitch under the skin is used or a series of separated stitches or metal skin clips rather like little staples. A top up to the local block is given. A dressing is applied.

You are then woken up and I write some notes on how things went and what we found. I call any relatives who may be waiting for news – please, when I come to do your consent form before the surgery, give me the name and number of anyone you would like us to call.

Removal of the suture/clips if it is required occurs at approximately 10 days. This can be done either at the hospital or at your GP’s surgery or at home by district nurse. If we have used clips, we will give you a clip remover before you go home.

Should you have a fusion or disc replacement?

No one should consider this procedure unless they have serious symptoms which have persisted for a long time and for which all other possible treatments have been tried. What you have just read explains that the surgery is major and the failure rate high. If you have discogenic pain you need to feel desperate and that you have exhausted the alternatives. The results of each are similar but as we have discussed above certain factors will steer us to one or the other.

In general, we strive to preserve and restore movement though on occasions this is either not possible or not sensible.

Risks

No procedure is without risk though this is routine surgery which rarely causes harm and usually works very well.

Please click here for details regarding the risks involved in this procedure.

The Risks

Complications of any operation and indeed any long period spent in bed include chest infection and blood clots forming in the deep veins of the legs (deep venous thrombosis or DVT). Parts of the blood clots may break off and fly up to the lung where they block the blood flow (Pulmonary embolus or PE). Very rarely people die from these blockages. You may have heard of these complicating long plane journeys. We can reduce the incidence of these by giving you injections to thin the blood, supportive stockings (which I request you wear at all times whilst in hospital) and compression pumps on the legs worn while in bed. We use the stockings and pumps in theatre but do not start the injections until 24 hours after the surgery so as not to provoke bleeding into the fresh wound.

There is a risk to life and limb. Any anaesthetic and any operation may kill you. Any spinal surgery may paralyse you which in the instance of a lumbar operation will mean loss of all leg, bowel, bladder and sexual function. At its worst, this may be complete and permanent. Such disasters are extremely rare and are in the order of the risk of your being run over by a bus. People do get run over by buses but it is exceptionally rare. Of course, if you do not have the operation the disc may fully prolapse. Again, I see this though very rarely - these “buses” associated with the natural history of the condition are indeed extraordinarily rare and you can usually see them coming and so take evasive action.

The “cauda equina syndrome” is the term used to describe paralysis of this part of your nervous system. The patients usually have a phase of excruciating pain followed by numbness, paralysis and an inability to pass urine which classically is painless. i.e., you know you have an overfull bladder but it does not hurt – “painless retention”. An early warning may be numbness around the private parts/perineum.

If you notice anything like this you need to see a doctor, any doctor – don’t wait for me - immediately. This syndrome is a surgical emergency. You need to have the nerves decompressed immediately i.e., that day / night.

Nerve root injury affecting just the nerve that passes out from the spine at this level - it is not quite so rare but is far from common. Obviously, the nerve root is handled during the procedure and even though microsurgical techniques reduce this to a minimum the risk of an individual nerve being permanently lost remains. It is low – less than 1 %. This might mean that the ability to stand on tip toe is lost or to lift up the foot (a foot drop) results. Again, if you do not have the operation, pressure from the pathology itself may do this anyway.

The spinal nerves are contained in a sack and this is filled with fluid secreted by and in communication with the brain. As the disc fragment presses directly on this sack it may leak cerebrospinal fluid during the course of the operation. This should not adversely affect the outcome of the operation though does mean you will need to lie flat for five days as described above (See CSF Leak section above). Nearly always the leak can be seen during the surgery and therefore I will give instructions for you not to be mobilised for the five days. If you are told you may get up then I have not encountered a leak. This occurs about 1 in 20 times though is more frequent when patients have had surgery before.

Failure of an operation to achieve its intended goal is always possible. In this instance, it will mean the persistence of back and leg symptoms as they were before. In those of you having this surgery for “discogenic” back pain, there is a failure rate of up to 50%. That is to say half of these procedures fail. In addition, even in the successful cases persistence of some non-disabling levels of back pain is common. It is not uncommon for a degree of pre-existing weakness and numbness to persist particularly if it was severe beforehand. The longer they have been present the more likely this is.

Recurrence of symptoms may occur. That is to say you may get better only for things to get worse again later. This is obviously a variety of “failure” as above. There are a number of reasons why and again this may be in the form of back or leg pain. Back pain may occur in acute bouts and can be minimised by your being diligent with the post-operative physiotherapy. Leg pain may arise from narrowing of the spinal canal developing at an adjacent level or indeed at the original level, scarring occurring around the nerve roots at the original level and damage caused by the original compression leaving the nerve root hypersensitive as it attempts to recover in the post-operative months. Finally, the instrumentation may irritate the nerves and muscles of the spine. Usually, it is an element of each of these pathologies which operate together to cause recurrent leg or back pain. A degree of pain is almost universal. Precisely how severe and how often is still a matter for some debate.

To find out a true recurrence rate thousands of patients need to be followed for tens of years and for none to drop out during that time. There is no perfect study but it is my impression from those studies that have been done and from my experience, that perhaps 1 in 5 of the discogenic group eventually have substantial persistent or recurrent trouble.

Deterioration is a possibility. Operations can make you worse, can do you harm or may leave you with new problems to cope with. This is rare and I suspect deterioration directly as a result of the surgery probably affects around 1% to 2% of patients – certainly less than 5% or 1 in 20. Quite a few patients may have a transient increase in numbness or weakness though persistent significant problems are rare indeed.

Wound infection can occur with any operation. In the spine it is rare as there is so much muscle covering it. Muscle fights infection well. However, if an infection ever sets in the effects can be very serious. The risk is around 1%. Diabetic patients are at a higher risk of this. Superficial wound infection may be successfully treated with antibiotics alone. However, if the infection gets deep into the wound and affects the metal work then this often eventually has to come out. This may take months to treat.

Infertility: A problem arises with anterior surgery at the L5/S1 level, (the bottom disc), in male patients. Around 10% will develop infertility from a condition called retrograde ejaculation. Patients have normal erections and will orgasm but the sperms will flow into the bladder rather than down the penis. This is because the nerve supply for this function passes over the front of the disc. They are too fine to see. This tends to mean that at this level we avoid anterior surgery – perhaps instead a posterior fusion is recommended. In the event that anterior surgery is essential, it may be possible to store sperm. This is not a complication that occurs at other levels.

Informed consent

Before you have a procedure of any kind, however trivial you may feel it to be, you must be fully aware of the possible and likely consequences. You have to sign a consent form in which you state that you are fully aware. We will go over this with you in your consultation. Do not sign the consent form for a procedure with us unless you feel fully informed of its aims and risks, as well as the alternatives. Please make sure you are fully content with everything set out in our Informed Consent for Treatments: Operations and Injections.

Click here for details of an extract.

Obviously, you must know what the aims and risks of any operation are. We will document in the notes that we have explained these to you as it is routine to do so. Do not sign the consent form if you feel we have not.

We will write something like this in your notes:- make sure you feel it is true

“I have explained the aims and risks of the procedure including those to life and limb (i.e. death paralysis and disaster), of failure (the procedure does not work), recurrence (you get better but it comes back) and deterioration, (you are made worse), of death, paralysis, wound problems, of nerve/ nerve root injury, as well as the likely natural history of the condition (what happens if nothing is done), the possible impact of alternative managements and treatments, along with the usual post procedure recovery and its variants (i.e., how much time off from work, what help you will need at home, what the wound care is).”

These are all things you will need to have had covered. Again, do not sign the consent if you are not sure

What happens if you don’t have it done?

The “natural history” is what happens when nothing is done and this must be compared with the scale of risks associated with the procedure.

Please click here for more details.

Discogenic pain will often eventually settle. If you are having surgery before a year there needs to be a good reason – progressive motor or sensory loss, worsening rather than consistent or declining pain, or an associated narrowing of the spinal canal of such severity that it threatens paralysis. You should know what the reason is for such a rapid progression to fusion surgery. However, if after this time there is no clear pattern of improvement in symptoms many of you are stuck at least for a long time. Many of you will have had a very gradual onset of symptoms perhaps years ago. Again, in these circumstances it is likely that you are stuck.

From this, you can appreciate that there are virtually no circumstances where you should feel rushed into a these operations. They are elective operations which should be done after very careful consideration.

What alternative procedures are there?

Much of this is covered in other information sheets and will have been the subject of our previous discussions. Essentially any operation is always the last resort.

Instead you could try injections or further conservative treatment (physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic, acupuncture, tablets and time.) Obviously, I will usually have formed the view that these are unlikely to bring you to comfort any time soon. Occasionally, I will have warned you that bad paralysis of nerves may occur if things are left and in these circumstances there is little choice but to proceed. The majority of you in this urgent situation will have very severe narrowing of the spinal canal and progressive weakness and numbness. However, this is an unusual situation. For the majority, it is pain that drives the surgery. In these circumstances, you have to feel that the degree of pain warrants the risk and effort involved in having the operation.

What happens if you don’t have it done?

The “natural history” is what happens when nothing is done and this must be compared with the scale of risks associated with the procedure. Eventually, many people’s troubles will settle though again good data is hard to find. A general rule of thumb is that within the first six to ten weeks spontaneous resolution occurs for about 95% of patients – or at least a substantial and consistent decline in symptoms is evident. If you are having surgery before this time there needs to be a good reason – progressive motor or sensory loss, worsening rather than consistent or declining pain or a disc prolapse of such immense proportion that it threatens paralysis. You should know what the reason is for such rapid progress. However, if after this time there is no clear pattern of decline in symptoms many of you are stuck at least for a long time. Into this picture it may be reasonable to integrate any social, personal, occupational and domestic pressures.

Discharge

Most people go home at about a week.

Please click here for more details.

However, there is no rush and you should stay until you can manage the journey home, life at home and have not needed the pain relief drip for 24 hours. If you live a long way off, live on your own or have a dependant family you will need to stay for longer. Occasionally, the less able who live alone might sensibly use a convalescent facility. Equally, some go home on day four or five though if you are an early leaver you should rest at home much as if you were still in hospital.

Don’t forget to take your X-rays and scans with you.

Remember there is no rush – go home when you are ready. You should be able to tick certain boxes:

- be able to mobilise and more or less dress yourself

- to have passed urine and opened your bowels

- to have tried some stairs with the physiotherapist

- to be able to manage on just oral medication and pain relief

- to be able to cope with your journey home

- to be able to survive comfortably with your personal home circumstance

Often day two and three are worse than day one in terms of pain. We tend to plan the precise discharge time on the ward rounds on day three or four.

How to get home

The front passenger seat in a standard car is fine. If the journey is long get out of the car every hour and do some simple stretches. Then get back in the car and carry on. It is often sensible to take some tablets before you leave the ward. Go to bed when you get home regardless of how well you feel.

Done once, even a long journey is OK. This is not a licence to drive every day.

Post-operative back care

Before you go home after your operation, we will have discussed some details of how to care for your back in the weeks that follow. Below is a general summary.

If you feel you are developing unexpected troublesome or worrying symptoms, do not hesitate to call my office or the ward staff, who will be able to guide you or if necessary contact me. If troubles arise out of hours, call the hospital and ask for the sister in charge.

Please click here for more details.

Post-operative back care

Physiotherapy

You may well have been given specific instructions by the hospital’s physiotherapist. Indeed, you are likely to be given a sheet with diagrams of various exercises. The precise details of these exercises and how often they should be done will vary from one individual to another. However, these details are of less importance than your response to them. That is to say, if you develop pain on doing these exercises, you should stop them. In the first few weeks all that can occur is the simple healing process. Physiotherapy maintains your mobility during this time but should not be allowed to interfere with the healing process. Therefore, if it hurts, you should stop and you should not be anxious if, as a result, you are quite stiff by the end of this early period. Physiotherapy begins in earnest around the fourth to sixth week when the wound and back will be stable enough to allow real progress to be made.

Exercise

The aim here is to do small amounts but often. For most of the first week, you will either be in hospital or should be pottering about inside your home. For the second week, the amount of activity undertaken should essentially be unchanged. You should simply be moving about as if you were in fact still in hospital. It would be perfectly reasonable to fix your own meals and to look after yourself though you should not be doing housework or looking after others. You may go out for short walks. From the second week onwards, light exercise may be taken. You may go on very short car journeys (10-15 minutes) and go out for longer walks. Prolonged outings, lengthy or frequent trips to the office will be bad for you. Problems most often arise when patients do a little too much a little too often, i.e., one trip to the office may be alright but three cause troubles.

Sitting

You are better to be standing or lying following back surgery. If you wish to sit, a high, upright dining room style chair is the most appropriate. It is certainly reasonable to start sitting for your meals when you have gone home but it is sensible to stand up and stretch between courses. This should be back to normal around about the four to six week mark. However, it will always be advisable to avoid prolonged periods sitting and very soft or low armchairs

Baths and showers

You should in the early days avoid baths as lying curved in them is likely to cause back pain. In addition, any waterproof dressing is unlikely to keep out all water if submerged. Showers or and assisted standing baths are better. Please don’t fall over.

Sex

If it hurts, don’t. If you think it will hurt, don’t - until of course you think it won’t and it doesn’t.

Wound care

You should not get the wound wet until the day after the sutures have been removed. It is perfectly reasonable to have a shower, providing the wound is covered with a waterproof dressing. The ward will provide you with this before you leave. In general, we like to change the dressings on wounds as infrequently as possible. The wound should be kept dry and a non-waterproof dressing used so that the wound may breathe. That is to say, whilst you should cover the wound in a waterproof dressing for showers this should usually be replaced by a dressing which breaths. Cunningly, there are now dressings which let moisture out but not in. These are ideal. Ask the nursing staff/my spinal nurse which it is you have on.

Removal of Stitches

The stitches, of which ever type, should be removed at or shortly after the tenth day. Most often a nurse linked to your G.P. or the district nursing service do this. If you are near one of my hospitals you may be able to have these removed there. You need to have agreed an arrangement for this to be done before you, leave hospital - our ward nurses who will liaise with your GP, district nurse or one of the local hospitals as is appropriate. I often use a single stitch which runs under the skin and which can be pulled from one end. (Get an adult to help you.) I also usually put steristrips (small sticky tapes) across the wound and two in parallel with the wound to hold the stitch ends. The ones holding the stitch ends need to be pulled off and then the suture can be removed. For some I use skin clips. These are like small staples and are removed with a special clip remover. You will be given a clip remover by the ward for you to give to the nurse who will be doing the removal.

Bending, lifting, carrying

In the first few weeks, you should not be doing this. The physiotherapy, which will begin about the fourth to sixth week, will teach you how to bend correctly and how best to lift. It should certainly be something that you keep to a minimum in the first months.

Driving

In the first few weeks, you should be driven i.e., you should not drive the car yourself. In the weeks that follow, you should limit journeys to short periods. As physiotherapy commences and progress is made, you may gradually start to extend this. In general, it is best to have the car seat set as high and as upright as possible. If you are becoming uncomfortable you should stop, get out and do some light stretches before continuing.

Sports

You should not do this until we have reviewed your progress. It should be deferred until you have completed the fitness programme that only begins with the physiotherapy at the fourth to sixth week and is likely to take a further four to six weeks at least.

Corset

This needs to be on at all times when upright if you had a fusion but is not needed in disc replacement surgery. If you have had both I will advise. Corsets are worn for the first 4 to 12 weeks – 6 on average.

General philosophy

The aim is for you to avoid things which aggravate your pain. Once recurrence of back and leg pain has occurred, it is much more difficult to get it to go away. It is much simpler to avoid it in the first place. If in doubt, err on the side of caution. You can do most things after the first week or so. However, you will not be able to do much of them. “Can I drive?”, “pick up the baby?”, “go into the Office?” or “fly?” are all frequently asked questions. The answer is usually yes BUT not very often. It is not so much what you do but how often you do it. For example, it is O.K. to be driven home a few days after the surgery but that does not mean it is alright to drive each day into the office.

Follow-up

The usual routine is to see patients three or four weeks after discharge and it is at that point that we can start the physiotherapy. This will need to be near to home though later may need to move nearer to work. I usually then see you after another six weeks and then a further three months. A review at a year with a final X-ray is often sensible.

Return to work

Most of you are heading back at around 6 weeks.

Please click here for details of how this is safely done.

A safe return to work

This may reasonably be anytime between four and twelve weeks post surgery. This might seem like a ridiculously wide window and certainly I will advise you more precisely. In fact, some patients are back at work inside two weeks and others still off at four months. A brick layer commuting 50 miles by car each way will take longer than a librarian working next door to home. (Actually, the former might sensibly try becoming the latter).

Whatever the work, a gradual return is best. A suitable regime for an average office worker with a reasonable commute might be: – perhaps two half days the first week (Tuesday and Thursday), three the second (Monday Wednesday and Friday) and four the fourth (Monday, Tuesday and Thursday, Friday). Work five half days the next and then start to increase the length of the days. It is important to keep up the physiotherapy during this phase.

Done in a graduated way the return to work is a very positive part of your rehabilitation. It needs to be in your control and with the encouragement of your employer. If they will put up with you being part-time and unreliable they will see you sooner.

If, by contrast, your job is one whereby you have to be there fulltime and reliably or not at all, it will take longer. Then the job is not a part of the rehabilitation but the hurdle rehabilitation has to prepare you for. You will get back later as you need to fully recovered before starting. If you have a long commute your return will be further delayed.

The average commute time for many patients is in the region of one hour each way. From the spinal perspective, that is a two hour physical job in addition to your real work. Days spent working from home help.

Discuss this advice with your employer and make a plan. Obviously, the best laid plans may change due to circumstances and we will be able to advise on how likely your plan is to come off at the first out-patient session post surgery i.e., at about the four week mark.

Results

This surgery usually works and is usually safe. However, the failure rate is not uncommonly found around the 30% mark. In some series, it is lower but in others as high as 50%. You should not have this surgery if you are not at terms with the possibility of the surgery failing.

What do you do in the event of problems?

If, once you have got home, problems arise, help is available from a number of sources.

Please click here for details of who and how to call.

Where can I get help?

First, you may ring my office number. If, it is during working hours, this is certainly what you should do. My secretarial staff will be able to contact myself, my clinical assistants or our spinal nurse and obtain advice for you. If, it is out of hours, you may also ring this number and the machine will tell you what to do in the event of an urgent enquiry or you may leave a message.

Second, you may ring the hospital and ask to speak to my Spinal Nurse. In her absence, you should ask to speak to the hospital’s Duty Manager or to the ward staff.

You may of course contact your general practitioner or any emergency service should you so wish or if the other avenues fail.

We do not provide a 24 hour emergency service but can respond on most occasions.

Costs, Codes and Authorisation

A separate information sheet is available which covers all aspects of this. Please obtain this and read it before you confirm your surgery. The costs of private surgery are considerable and if you are hoping to use insurance you will need to obtain authorisation from your insurer and register this with us prior to admission. Some insurers/policies may not pay all surgical, anaesthetic or hospital fees. All costs remain your responsibility even if your insurer has agreed to help/pay direct. There are usually three bills you need to know about; the hospital, the anaesthetist and the surgeon. You are responsible for ensuring all are paid.